Why Your Midlife Muscle Matters More Than You Think

Can you hold a plank for 60 seconds? Hang from a bar for a minute? Perform 10 push-ups or complete 15 squats in 30 seconds?

You may answer yes to some, all, or none of these but what matters is not the test itself. Being able to perform movements like these reflects functional strength, which is strongly associated with lower all-cause mortality and better long-term independence in women. Muscle-strengthening activities, including exercises such as push-ups and squats, are associated with a 15–24% lower risk of all-cause mortality in large observational studies, with women often deriving greater survival benefits from equivalent physical activity doses compared to men (H, Ji et al., 2024; Leong et al., 2015; Kamada et al.,2017).

Midlife represents a critical intervention window. The muscle you have and the strength you maintain during this stage of life plays a decisive role in metabolic health, resilience, and independence later on. For women, this period represents an opportunity to influence how we age and how well we function in the decades ahead.

Why Midlife Muscle Matters for Women

Muscle is not just tissue which allows us to move. It is a metabolically active organ that plays a central role in physical function, glucose regulation, bone health, and recovery from illness (Pedersen & Febbraio, 2012). From around the fourth decade of life, muscle mass and strength begin to decline. Importantly, strength tends to decline faster than muscle size, and this process accelerates with age. These changes increase the risk of sarcopenia, falls, disability, and loss of independence (Kim & Choi, 2013; Lai et al., 2025).

Muscle as the Foundation for Later-Life Function

In women aged 40–64, higher muscle strength and quality are consistently associated with faster walking speed, improved chair-stand performance, and better overall functional capacity independent of age, body weight, or self-reported physical activity levels (Finnegan, O et al.,2021).

Muscle strength, particularly grip strength and lower-body strength, is also strongly associated with reduced all-cause mortality in women (Leong et al., 2015; Celis-Morales et al., 2018).

In practical terms, midlife muscle lays the foundation for how well we move, function, and live later in life.

Hormones, Menopause, and Muscle Health

Estrogen plays an important role in maintaining skeletal muscle mass, strength, and repair capacity. During perimenopause and menopause, evidence suggests that declining estrogen contributes to reductions in muscle mass and neuromuscular function (Sipilä, S et al.,2020; Juppi, H et al., 2020). Lower estrogen levels are associated with impaired muscle regeneration, altered mitochondrial function, and reduced muscle quality, which may help explain why many women experience accelerated strength loss during midlife (Ribas et al.,2016).

Observational studies have also reported associations between lower muscle mass and greater severity of menopausal symptoms. These findings are correlational and do not establish causality, but they highlight the close relationship between hormonal change, muscle health, and overall wellbeing (Wang et al., 2025).

Metabolic and Cardio-metabolic Protection

Skeletal muscle is the body’s primary site for insulin-mediated glucose uptake. Loss of muscle mass and strength combined with declining estrogen contributes to worsening insulin sensitivity and increased cardio-metabolic risk in midlife women (DeFronzo & Tripathy, 2009; Ribas et al., 2016). Research shows that low muscle strength combined with high visceral fat more than doubles the risk of developing prediabetes or type 2 diabetes, compared with high visceral fat alone (Wong et al., 2024; Srikanthan & Karlamangla,2011). Preserving muscle mass and mitochondrial function is therefore central to maintaining metabolic health and reducing chronic disease risk during midlife and in the future.

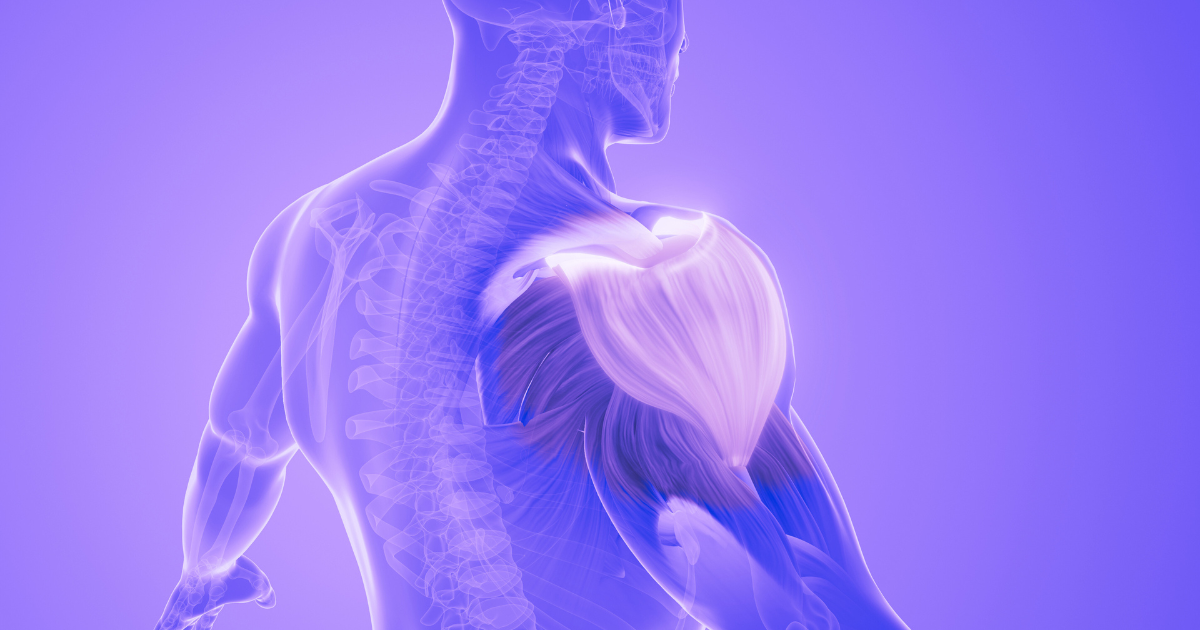

Muscle, Bone, Balance, and Falls

Muscle and bone are functionally interconnected. Muscle contractions provide mechanical loading that helps maintain bone strength and microarchitecture, while stronger muscles improve balance and postural control (Daly et al., 2013). As women age, they experience parallel losses in muscle and bone, increasing fracture risk. Muscle strength, particularly grip strength and chair-rise performance, is positively associated with bone parameters and lower fracture risk (Li et al., 2018).

Resistance training improves muscle strength and bone mineral density, especially at clinically relevant sites such as the hip and spine (Watson et al., 2018). Improved muscle strength also reduces fall risk by enhancing balance and protective responses (Sherrington et al., 2019; Choudry et al., 2025 ).

Together, these findings highlight how closely muscle and bone health are biologically linked and that regular resistance training is an important strategy for midlife women to simultaneously build bone density and improve the balance needed to prevent fractures and maintain long-term independence.

Practical Implications

Taken together, the evidence points to a clear conclusion: muscle in midlife is protective, not optional. For women, this means shifting health and fitness goals away from weight loss and toward strength, function, and resilience.

Resistance training should form the backbone of physical activity during midlife (and beyond).

Current evidence supports a minimum effective dose of 2–3 full-body resistance training sessions per week, focusing on compound (or full body) movements such as squats, hip hinges, pushing and pulling exercises, loaded carries, and core stability work (Isenmann et al., 2023). Progressive overload, i.e gradually increasing resistance over time, is more important than high repetitions or constant variation. Adequate recovery is equally essential.

Protein needs increase with age due to anabolic resistance. For physically active midlife women performing resistance training 2–3 times per week, evidence supports a daily intake of 1.2–1.6 g/kg body weight of high-quality protein, distributed evenly across meals (Jäger et al., 2017; Bauer et al., 2013). Proteins are considered “high quality” when they contain all essential amino acids and are efficiently used by the body. Animal proteins, such as eggs, lean meats and poultry, fish and seafood and dairy products, generally have higher biological value, but well-planned plant combinations (i.e. tofu and soy products, legumes and beans, nuts, seeds and wholegrains) can also adequately meet needs. In addition to adequate protein consumption, creatine monohydrate supplementation has been shown to modestly enhance strength and training adaptations in women, with randomized trials demonstrating greater strength gains and enhanced exercise performance when combined with resistance training compared with placebo. (Azevedo et al., 2022)

Evidence also suggests that muscle built and maintained in midlife functions as a critical physiological reserve, helping support recovery from illness, injury, and age‑related stressors, because declines in muscle mass and function (sarcopenia) are strongly linked with frailty, reduced resilience, and poorer clinical outcomes in later life (Larsson et al., 2019). Building and maintaining muscle in midlife is not a vanity goal; it is a health strategy. The strength you build now directly influences your independence, resilience, and quality of life in the decades to come.

Key Takeaways

Functional muscle strength in midlife is linked to lower mortality and greater long-term independence in women.

Midlife is a critical window to build and maintain muscle, shaping metabolic health and resilience later in life.

Skeletal muscle plays a central role in metabolism, balance, bone health, and recovery from stressors.

Hormonal changes during menopause may contribute to muscle decline and more severe menopausal symptoms, underscoring the importance of strength training.

Resistance training performed approximately 2–3 times per week effectively improves muscle strength and counters age-related muscle loss in women.

The scope of this article is to share current evidence which supports the important role of muscle for women during midlife. It must be acknowledged that many of these principles are universal. Muscle remains a vital health asset for men and women alike, regardless of age, and it is never too early, or too late, to start building your physiological reserve.

We all rise together,

Isabelle Statovci | Monthly Blog Contributor, Jenerise | BSc Exercise Science, MSc NutrDiet-APD Senior Director - Clinical Science

References

Azevedo KS, et al. Creatine Supplementation Improves Muscular Performance and Muscle Mass in Older Women, 2022.

Bauer J, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for optimal dietary protein intake in older people: a position paper from the PROT-AGE Study Group, 2013.

Celis-Morales C, et al. Associations of grip strength with cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality: prospective cohort study of 502,293 UK Biobank participants, 2018.

Choudhary PK, et al. Effectiveness of Balance- and Strength-Based Exercise Interventions in Improving Physical Function in Older Adults, 2025.

Daly RM, et al. Exercise and bone health in postmenopausal women, 2013.

DeFronzo RA & Tripathy D. Skeletal muscle insulin resistance is the primary defect in type 2 diabetes, 2009.

Finnegan O, et al. Associations Between Lean Mass, Muscular Strength, Muscle Quality And Physical Function in Older Adults, 2021.

Gotshalk LA, et al. Creatine supplementation improves muscular performance in older women, 2008.

Isenmann E, et al. Resistance training alters body composition in middle-aged women depending on menopause status, 2023.

Jäger R, et al. International Society of Sports Nutrition Position Stand: protein and exercise, 2017.

Ji H, et al. Sex Differences in Association of Physical Activity With All-Cause and Cardiovascular Mortality, 2024.

Juppi H, et al. Role of Menopausal Transition and Physical Activity in Loss of Lean and Muscle Mass: A Follow-Up Study in Middle-Aged Women, 2020.

Kamada M, et al. Strength Training and All‐Cause, Cardiovascular Disease, and Cancer Mortality in Older Women, 2017.

Kim TN & Choi KM. Sarcopenia: definition, epidemiology, and pathophysiology, 2013.

Lai Z, et al. No independent association between dietary calcium/vitamin D and appendicular lean mass index in American adults: a cross-sectional study, 2025.

Larsson L, et al. Sarcopenia: Aging-Related Loss of Muscle Mass and Function, 2019.

Leong DP, et al. Prognostic value of grip strength: findings from the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study, 2015.

Li YZ, et al. Low Grip Strength is a Strong Risk Factor of Osteoporosis in Postmenopausal Women, 2018.

Pedersen BK & Febbraio MA. Muscles as endocrine organs: myokines and health, 2012.

Ribas V, et al. Skeletal muscle action of estrogen receptor α is critical for the maintenance of mitochondrial function and metabolic homeostasis in females, 2016.

Sherrington C, et al. Exercise for preventing falls in older people living in the community, 2019.

Sipilä S, et al. Muscle and bone mass in middle‐aged women: Role of menopausal status and physical activity, 2020.

Srikanthan P & Karlamangla AS. Relative muscle mass and insulin resistance, 2011.

Wang X, et al. Association between menopause-related symptoms and muscle mass index, 2025.

Watson SL, et al. High‐Intensity Resistance and Impact Training Improves Bone Mineral Density and Physical Function in Postmenopausal Women with Osteopenia and Osteoporosis: The LIFTMOR Randomized Controlled Trial, 2018.

Westcott WL. Resistance training is medicine: effects of strength training on health, 2012.

Wong B, et al.Individual and combined effects of muscle strength and visceral adiposity on incident prediabetes and type 2 diabetes, 2024.